A Hidden Problem For Retirement Planning

Retirement planning is a significant challenge to many investors. They must decide how much to save now to allow them to retire later and that problem involves assumptions about potential returns, the sequence of returns or the risk, the rate of inflation and the length of time the assets will need to be used for.

The Wall Street Journal recently highlighted the problem in terms that are facing government agencies around the country, “The pressures are coming from a slate of problems, and the longest bull market in U.S. history has failed to solve many of them.

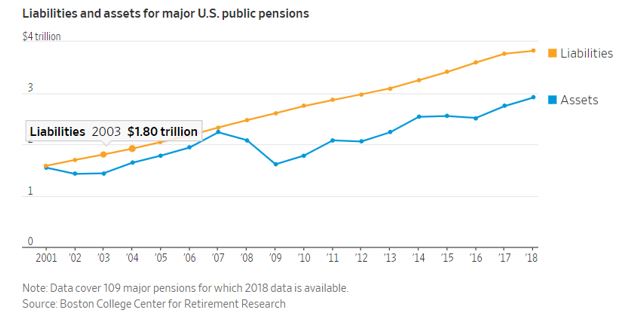

There is a simple reason why pensions are in such rough shape: The amount owed to retirees is accelerating faster than assets on hand to pay those future obligations. Liabilities of major U.S. public pensions are up 64% since 2007 while assets are up 30%, according to the most recent data from Boston College’s Center for Retirement Research.

Here is how it got that way:

The Financial Crisis Happened

Source: The Wall Street Journal

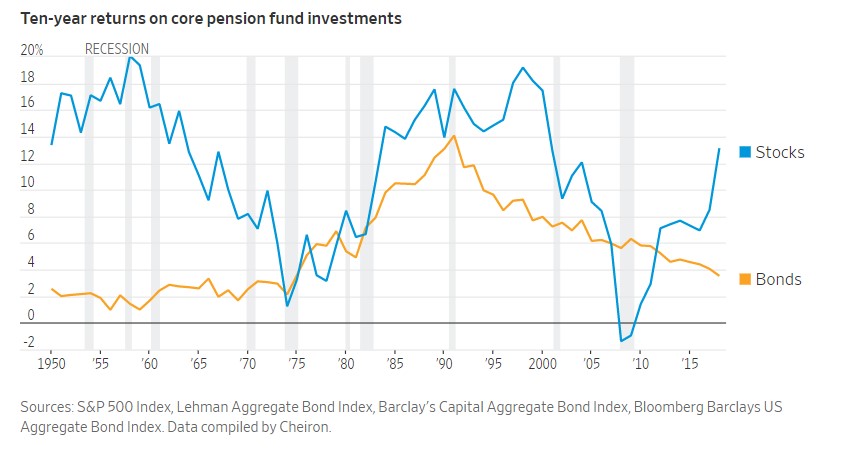

Public pension funds have to pay benefits—their liabilities. They hold assets, which grow or shrink through a combination of investment gains or losses and contributions from employers and workers. Those assets generally rose faster than liabilities for five decades starting in the 1950’s because government was expanding and the number of retirees was smaller.

In the 1980’s and 1990’s, double-digit stock and bond returns convinced governments they could afford widespread benefit increases.

But the value of their holdings—their assets—began to fall in the aftermath of the dot-com bust in the 2000’s, and the 2008 financial crisis followed soon after. State and local retirement systems lost 28% in 2008 and 2009, according to the Boston College data.

Source: The Wall Street Journal

“The first thing you have to do is make up what you lost,” said Sandy Matheson, executive director of the Maine Public Employees Retirement System. “And it takes years. And then you have to make up what you didn’t earn on what you didn’t have. It’s a pretty steep climb.”

Governments Fell Behind on Their Payments

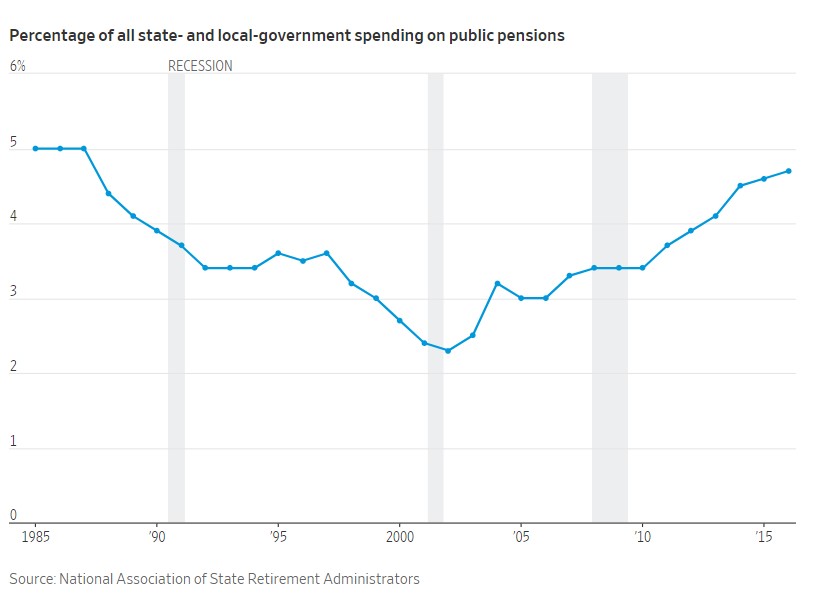

Cities and states set out to ramp up their yearly contributions to public pension funds as a way of making up for their investment losses.

Source: The Wall Street Journal

Some were able to keep up with those payments. But others weren’t as they struggled with lower tax revenue and increased demand for government services in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis. New Jersey made less than 15% of its recommended pension payment from 2009 through 2012. It now has a little more than one-third of the cash it needs to pay future benefits—despite robust investment returns in recent years.

These same problems could trip up individual investors.

Barron’s recently noted, The two most crucial questions in retirement planning—how long are you likely to live, and how much of your life will be spent in relatively good health?—have long been dismissed as unknowable.

But thanks to facial analysis, gene testing, and other new technology, advisors and investors may finally be able to get answers that meaningfully change the way they navigate saving for and living in retirement. And it has as much to do with your health as it does your portfolio.

Lifespan is arguably the crux of all financial planning, especially how much an individual should save for retirement, and how much he or she can safely spend once retired. It can also influence decisions related to timing Social Security benefits, buying annuities, and getting long-term care insurance.

Most people rely on crude tools, wild guesses and wishes to determine how long they’ll live. In a survey released by AIG Life & Retirement last week, 53% of respondents said their goal is to live to the age of 100.

Yet, the financial reality of living that long is daunting. In the same survey, the majority of respondents said they fear running out of money more than death itself.

The solution to managing longevity risk is to plan for it.

Lifespan tables are a starting point for many would-be retirees. But they are based on an entire population of people, and don’t take into account such factors as lifestyle, health, or family history.

Consider [an individual] who is 65. A standard lifespan table from the Social Security Administration suggests he’ll live to be 83. By his own assessment—which encompasses a number of factors, including biomarkers—he is on track to live into his 90s.

Calculators can give a more accurate read, but the results can vary dramatically depending on methodology and inputs. Anyone who goes this route should stick with a calculator that give results in probabilities rather than absolute numbers, says [one expert], who recommends the American Academy of Actuaries’ Longevity Illustrator.

Of course, life expectancy is just one component of longevity. Health span—how many of the years you have left will be spent in relatively good mental and physical health—should also be part of the equation.

“People say they want to live to be 100, but the number itself is less relevant than how healthy you are,” says ay Olshansky, a leading researcher in longevity and a professor in the School of Public Health at the University of Illinois.

Indeed, health doesn’t just determine quality of life, it is one of the single biggest wildcards for retirement planning.

This is where facial analysis—and other new technology, such as saliva-based tests for longevity genes and other biomarkers—could offer a more nuanced look at lifespan.

A new venture, Wealthspan Advisors, is gearing up to roll out a platform for advisors using the same technology that Olshansky and other researchers helped develop for the insurance industry.

Instead of simply asking clients how long they think they will live, planners ask a series of questions and take a photograph of a client’s face. From that photo, the program provides an estimate for both lifespan and health span, and illustrates how lifestyle choices will influence those outcomes.

“When you look young for your age, it usually means that you are aging at a slower rate,” Olshansky says, noting that the program isn’t fooled by makeup and cosmetic procedures.

Would-be retirees shouldn’t rewrite their financial playbook based on a single snapshot, but technology like this could offer a more accurate picture for planning.”